Vaza Toga: The Witch, the Infiltrator, and the Informant

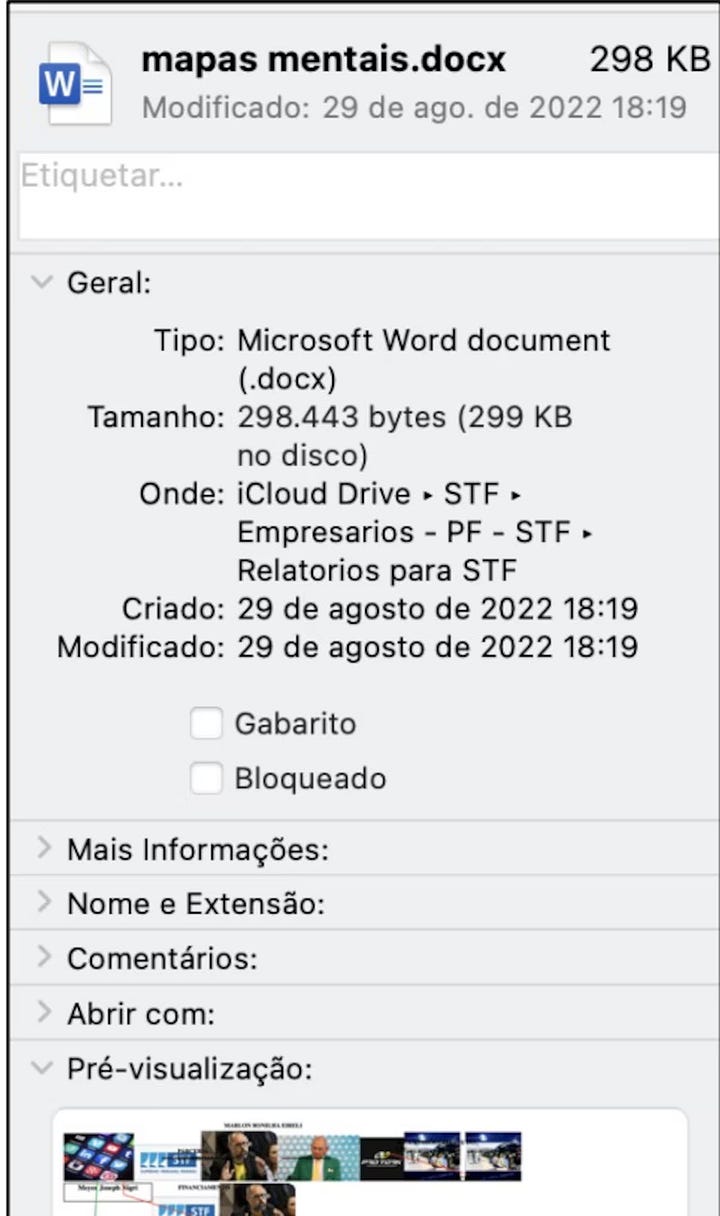

New leaks suggest that evidence was fabricated after a police raid on pro-Bolsonaro businessmen.

Our investigation had exclusive access to WhatsApp conversations between Eduardo Tagliaferro — then head of the Special Office for Combating Disinformation (AEED) at Brazil’s Superior Electoral Court (TSE) — and journalist Letícia Sallorenzo, known by insiders as “the Witch.” The messages reveal how, in August 2022, at the height of Brazil’s presidential campaign, private data from businessmen aligned with Jair Bolsonaro was secretly funneled to the court, just days after Justice Alexandre de Moraes ordered raids against them.

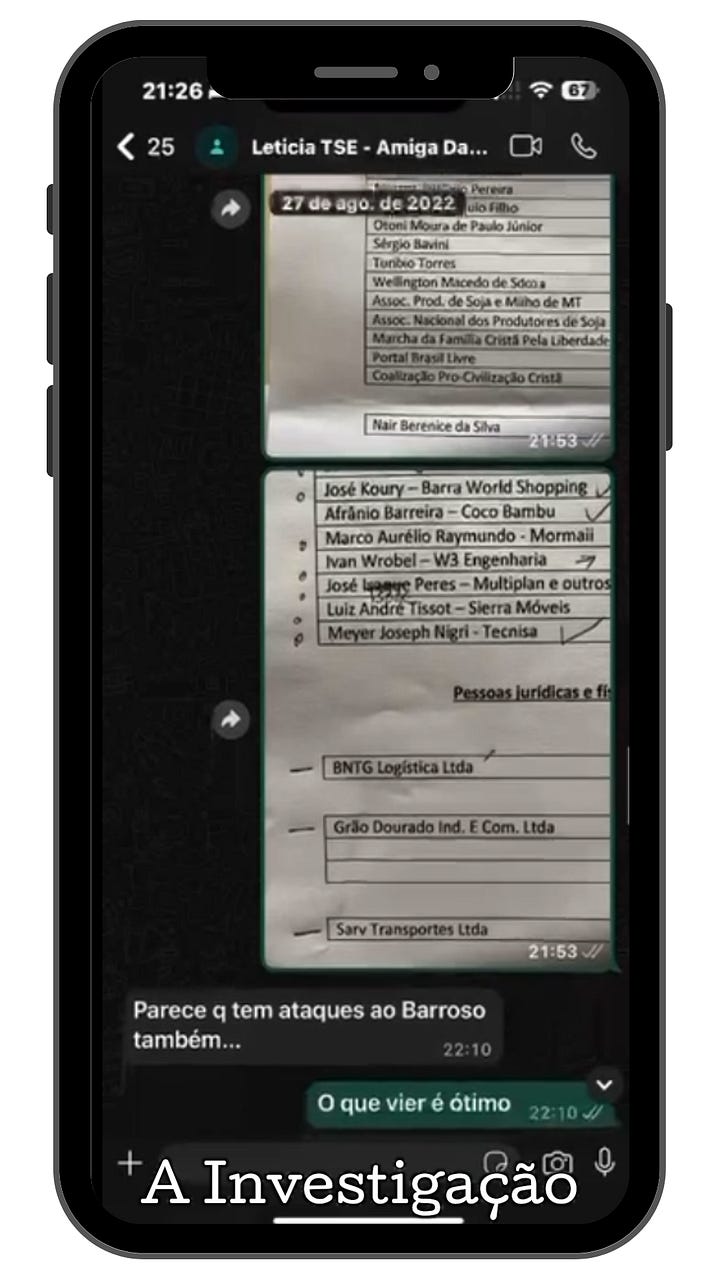

The August 23 operation, justified solely on the basis of a single news article, struck at the core of the business network seen as crucial for financing and digitally amplifying Bolsonaro’s campaign. With bank accounts and social media profiles frozen overnight, the group’s ability to mobilize was abruptly dismantled — silencing influential voices just days before the first presidential debate on August 28.

Moraes only archived most of the case a year later, once Lula was in office. The minister admitted that, for six businessmen, there was no evidence to justify prosecution. Two remained as targets: real estate mogul Meyer Joseph Nigri and retail tycoon Luciano Hang. Federal Police alleged that Nigri had direct ties to Bolsonaro in spreading anti-electoral system messages, while in Hang’s case Moraes claimed further analysis of his password-locked phone was still pending. Hang’s social media accounts remained suspended for over two years, until Moraes finally lifted the block in September 2024. The case file remains fully sealed.

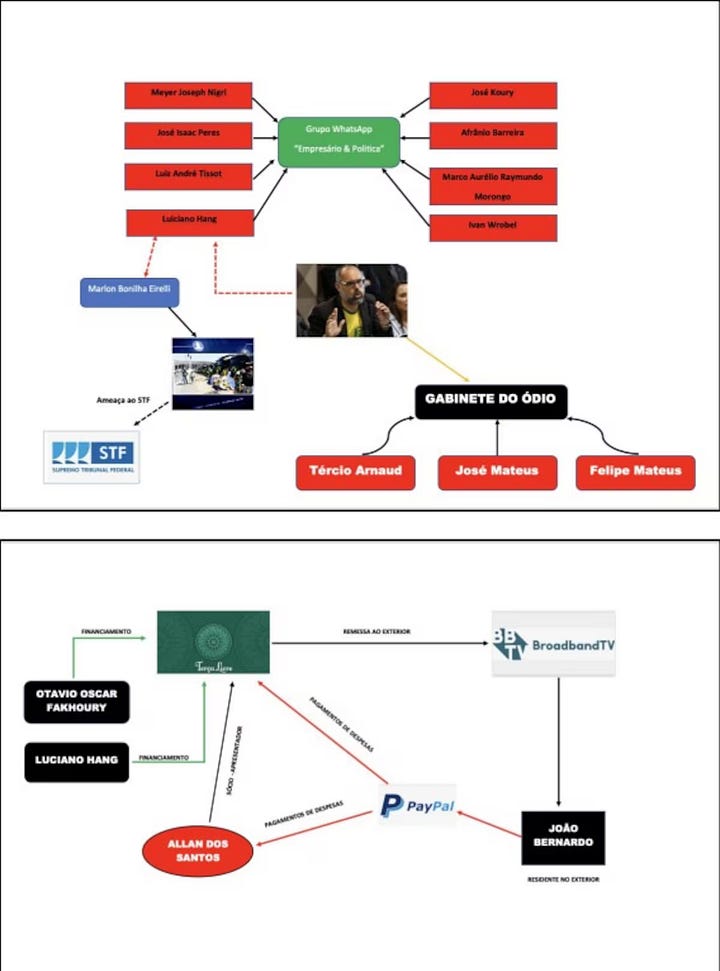

The leaked chats obtained by A Investigação show that, faced with flimsy evidence and growing backlash, Moraes pressured his staff to produce backdated documents. To meet the demand, Tagliaferro turned to Sallorenzo, who served as a bridge between the court and an infiltrator inside the WhatsApp group “Entrepreneurs & Politics.” A Investigação identified this informant as journalist Lucas Mesquita, who now works as an aide in Lula’s government.

In other words, an organized infiltration fed material directly to the TSE, with no formal chain of custody. Screenshots, membership lists, and even full exports of private conversations were handed over on the night of August 27, with the explicit aim of “reassuring the friend” — a reference to Moraes, anxious to quiet criticism.

The episode exposes how an informal collaborator, with ties even to Moraes’s family circle, funneled private information from a closed chat group straight into the court’s inner chambers. Instead of preexisting evidence that could have justified the August 23 crackdown, what emerged were retrofitted justifications, crafted to match the minister’s needs.

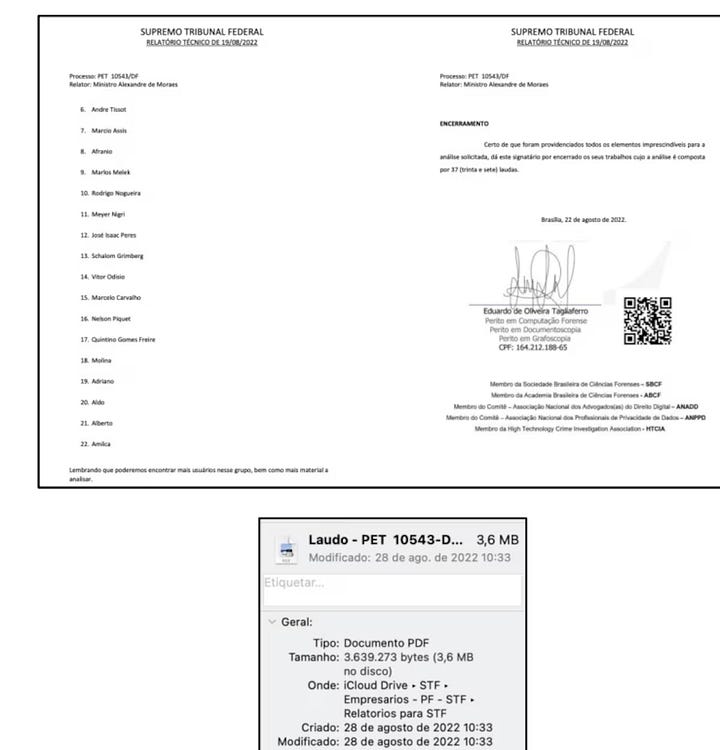

Far from a bureaucratic detail, this lends further credibility to Tagliaferro’s Senate testimony: that reports dated before the raids had in fact been assembled days later, with the help of external informants. The so-called “war on disinformation” thus appears less as a neutral defense of democracy and more as a political surveillance apparatus — one where the boundary between state authority and ideological activism vanishes.

One of Those Nights

On the night of Saturday, August 27, 2022, Justice Alexandre de Moraes was restless — and with reason. Just four days earlier, on August 23, he had ordered sweeping search-and-seizure raids against eight of Brazil’s top businessmen, deploying Federal Police armed with rifles and invasive warrants. The official justification for such a massive operation did not come from technical reports or long-standing investigations, but from a single news article published ten days earlier, on August 17, by columnist Guilherme Amado at Metrópoles. The story exposed messages from a private WhatsApp group called Entrepreneurs & Politics, in which some members voiced harsh criticism of the Supreme Court (STF) and were accused of discussing a potential coup if Lula were to win the election.

“I’d rather have a coup than see the Workers’ Party return. A million times. And for sure, nobody will stop doing business with Brazil, just like they don’t with many dictatorships around the world,” wrote José Koury, owner of Barra World Shopping. His comment — the most controversial among the leaked messages — made him Moraes’s prime target. Still, the statement reads less like an explicit coup plot and more like a frustrated outburst.

One businessman contacted by our team recalled that even the Federal Police agents tasked with carrying out the raids seemed uneasy. “They themselves didn’t know why they were doing it,” he said.

The operation — especially the targeting of Luciano Hang, one of Bolsonaro’s most prominent supporters — rattled the government and set off political alarms. The timing was striking: the country was in the middle of a fiercely polarized campaign, just days before the first televised presidential debate. Tensions mounted further because, that same day, Moraes had hosted Defense Minister Paulo Sérgio Nogueira at the Electoral Court for a one-hour meeting to discuss the military’s recommendations for the election — particularly adjustments to ballot-box integrity tests and coordination of security measures.

Moraes, aware that the public narrative could collapse, pressured his staff to produce documents that would serve as retroactive justification for his decision. According to his former aide Eduardo Tagliaferro — now a whistleblower — Moraes demanded that by Monday, August 29, he have updated material on the targets. That was the day he planned to lift the case’s secrecy in an attempt to calm public opinion.

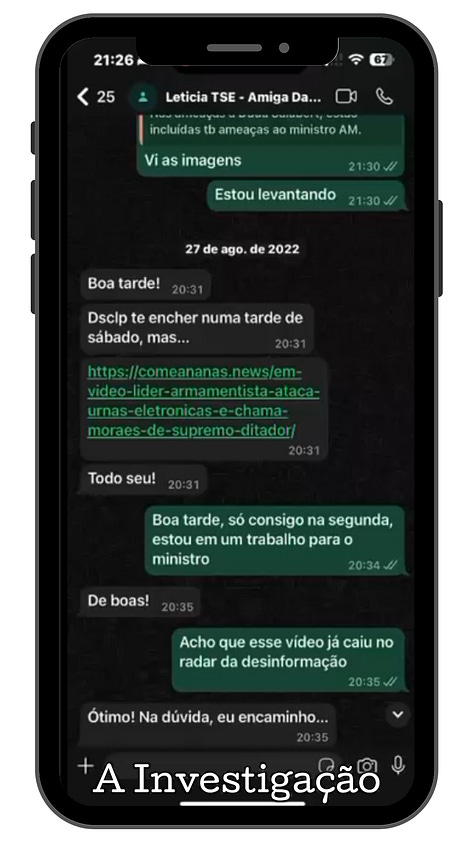

Tagliaferro, then head of the TSE’s Anti-Disinformation Taskforce (AEED), turned to an external collaborator known as “the Witch” — identified by A Investigação as journalist Letícia Sallorenzo. She acted as a bridge between the Electoral Court and an infiltrator inside the businessmen’s group. According to Sallorenzo, the same source had already provided material to Metrópoles journalist Guilherme Amado.

At 8:30 p.m. that Saturday, Sallorenzo opened her chat with Tagliaferro by requesting censorship of lawmaker Marcos Pollon (PL-MS), then still a pro-gun activist lawyer. She sent him a link from the website Come Ananás as reference. The censorship procedure was already so routine that it required no further instruction: “All yours!” she wrote. The article she flagged — later deleted but recovered by our team through an archive service — highlighted Pollon calling Moraes a “supreme dictator.”

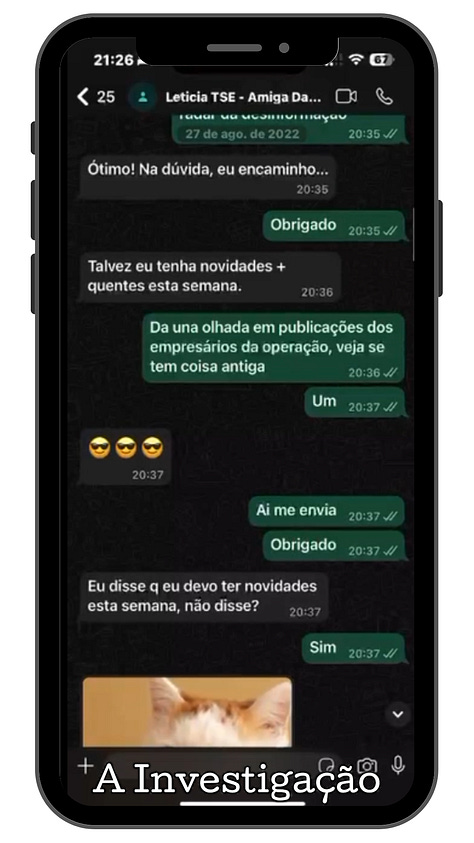

Tagliaferro replied that he was too busy, working for the minister on a confidential investigation. Still, he asked her to dig up older posts tied to the “businessmen.” Already aware of the context, Sallorenzo responded that she had “updates” and began forwarding screenshots from the group, showing names like Nelson Piquet, Flávio Rocha, and Luciano Hang.

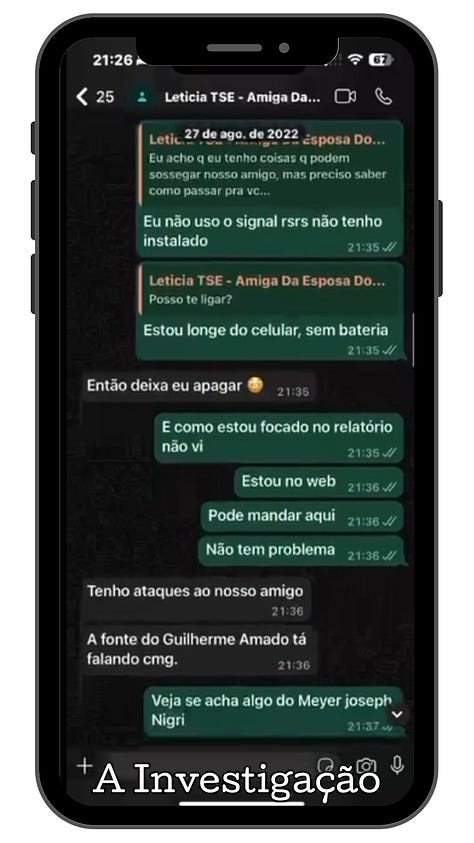

She then mentioned having sent additional material via Signal. Tagliaferro answered that he didn’t even have an account on the app. In other words, Sallorenzo — acting as an informal adviser to the Electoral Court — was passing private information into a Signal account without knowing who was on the other end.

The Main Targets

Throughout the exchange, Moraes’s aide was not just receiving the material Sallorenzo supplied — he was actively steering the flow of information according to the immediate needs of the minister’s office. He made clear which individuals and organizations were the top priorities. First, he directed attention to Meyer Nigri, real estate tycoon and founder of Tecnisa, one of the most heavily targeted businessmen. Next, he requested data on José Koury, owner of Barra World Shopping.

Tagliaferro also said he needed information on Judge Marlos Augusto Melek, then serving on the Labor Court in Araucária, in the greater Curitiba area. The following year, Brazil’s National Council of Justice (CNJ) removed him from the bench, accusing him of joining and commenting in the Entrepreneurs & Politics WhatsApp group. The CNJ argued that this conduct violated the ethical standards of the judiciary. Tagliaferro later circulated lists with several other names of people and companies flagged as targets.

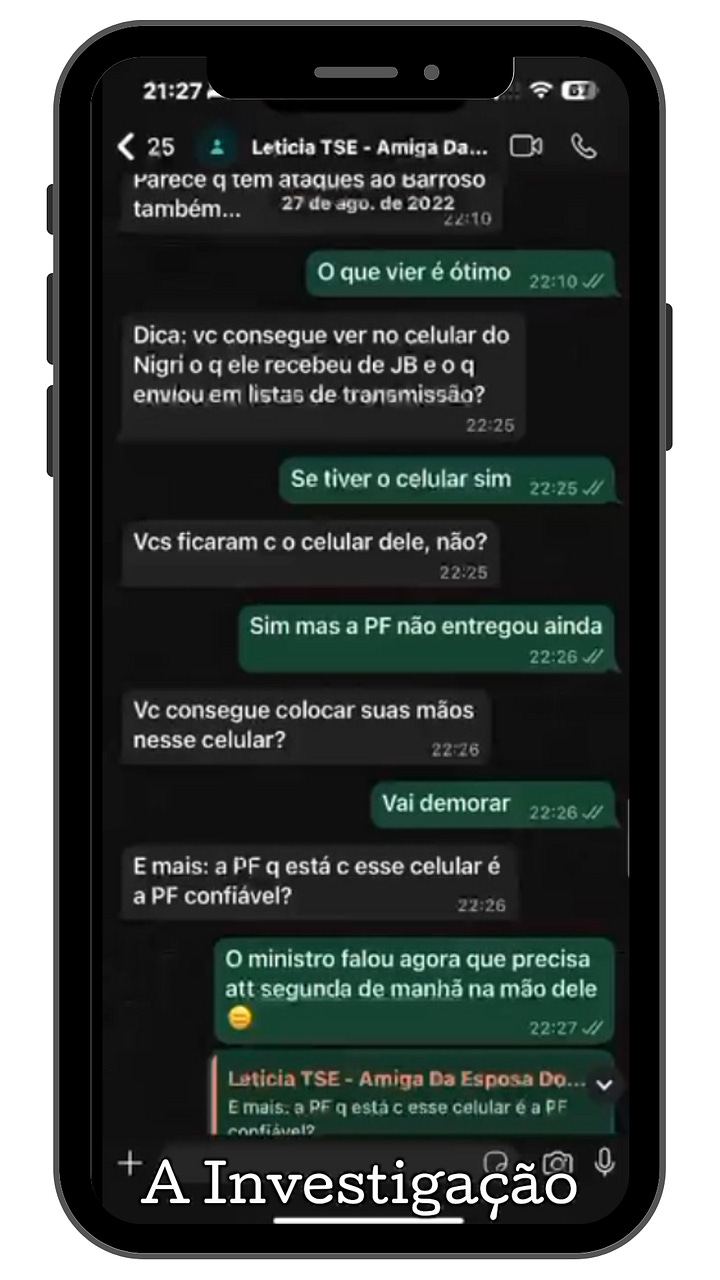

The “Trusted Federal Police”

At one point, Sallorenzo asked if it was possible to access the contents of Meyer Nigri’s seized phone — particularly the messages allegedly sent and received by Jair Bolsonaro in broadcast lists. Tagliaferro replied that it was possible, but admitted he had not yet received the device. Letícia then pressed: could he “get his hands on the phone”? He answered that it would still take some time.

That is when the most revealing passage appeared. Sallorenzo asked if the device was in the custody of a “trusted Federal Police team.” Tagliaferro confirmed it was — hinting at the existence of a parallel circuit within the PF, made up of investigators and agents deemed fully loyal to Justice Moraes.

Among the names mentioned was delegate Fábio Shor, a figure personally trusted by Moraes who would later play a central role in politically sensitive investigations carried out by the Federal Police. It was Shor himself who signed the report used to justify the crackdown on the businessmen — a report which, according to Tagliaferro, was written only after the raids had already taken place.

The Minister’s Wife’s Friend

Each request came with the expectation of new screenshots or contact lists, which Letícia Sallorenzo rushed to obtain from her infiltrated source. The goal was not only to gather “evidence,” but also to calm the boss: Moraes wanted the material in his hands by Monday.

“The minister just said he needs it by Monday morning. He even said it would be best if it showed comments after the raid and people leaving the group,” wrote Tagliaferro, suggesting that the demand came directly from Moraes.

Letícia replied that her source had already left the group, but had collected material up until the “exodus.” Tagliaferro said that was useful, but convincing the minister to wait would be difficult. “I’m talking with them to get more time. I’m trying to convince the minister. But he has to wait. This is very good for him,” he wrote.

After 11 p.m., Sallorenzo floated a bold idea: appealing to Moraes’s wife, Viviane Barci, to ask for more time to deliver the files. The suggestion underscored her closeness to the minister’s inner circle. In Senate testimony, Tagliaferro said Sallorenzo had access to private parties and ceremonies of the minister’s chambers that even assistant judges were not invited to. He described her involvement as motivated by personal devotion — “fanaticism,” in his words.

The trust was such that, as Letícia herself admitted, Moraes’s wife had her phone number. Even so, she showed caution: “Wouldn’t he be pissed if you involved his wife in this?” Tagliaferro agreed: “Better not mention it.”

The concern was not unfounded. Other incidents had shown that involving the minister’s family could spark harsh reactions. In July 2023, Moraes and his relatives clashed with the Mantovani family, Brazilian travelers on the same flight, in a shouting match at Rome airport. The case turned into a judicial offensive: the Supreme Court blocked release of the full CCTV footage, Federal Police carried out raids against the Mantovanis, and reports later challenged by independent experts raised suspicions of tampering.

Even so, Sallorenzo emphasized her proximity, offering to be contacted directly: “If he wants to talk to me, I’m available. Tell him if he wants to call me, his wife has my number. Letícia the Witch, from UnB…” The message — half mocking, half boastful — laid bare the privileged place she occupied in the minister’s informal network of trust.

The File Delivery

Throughout the conversation, Tagliaferro made a series of specific requests: screenshots showing hate speech, references to a coup, mentions of September 7 (Brazil’s Independence Day), quotes from Meyer Nigri, criticism of Supreme Court justices, or attacks on electronic voting machines. He pressed further, insisting that the source provide something that could be interpreted as evidence of a “coup,” even if from another context. This marked a turning point: the hunt was no longer limited to records from the group, but for any material that could retroactively support a pre-set narrative.

This detail is crucial. The coup-related remarks published in Guilherme Amado’s Metrópoles article were presented as the very trigger for Moraes’s search-and-seizure orders. The problem: the operation was carried out without the screenshots ever having been authenticated or forensically certified. In other words, the minister acted on material lacking formal validation. That is why new excerpts mentioning “coup” were seen as Moraes’s salvation: a way to reinforce — even retroactively — the shaky justification of an already controversial decision.

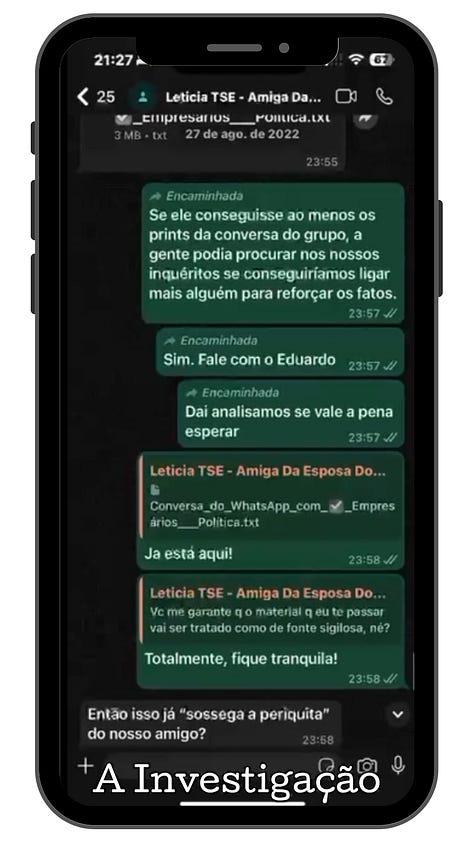

Under pressure, Letícia appeared to lose patience. Until then, she had acted as a bridge between the infiltrator — identified by A Investigação as journalist Lucas Mesquita, now an aide in Lula’s government — and Moraes’s chambers, passing fragments from the Entrepreneurs & Politics group. But as Tagliaferro’s demands intensified, she decided to cut out the middle step: at 11:55 p.m., Letícia sent the entire chat archive, a 3 MB “.txt” file. Along with it, she asked only for assurance that her identity as source be kept secret.

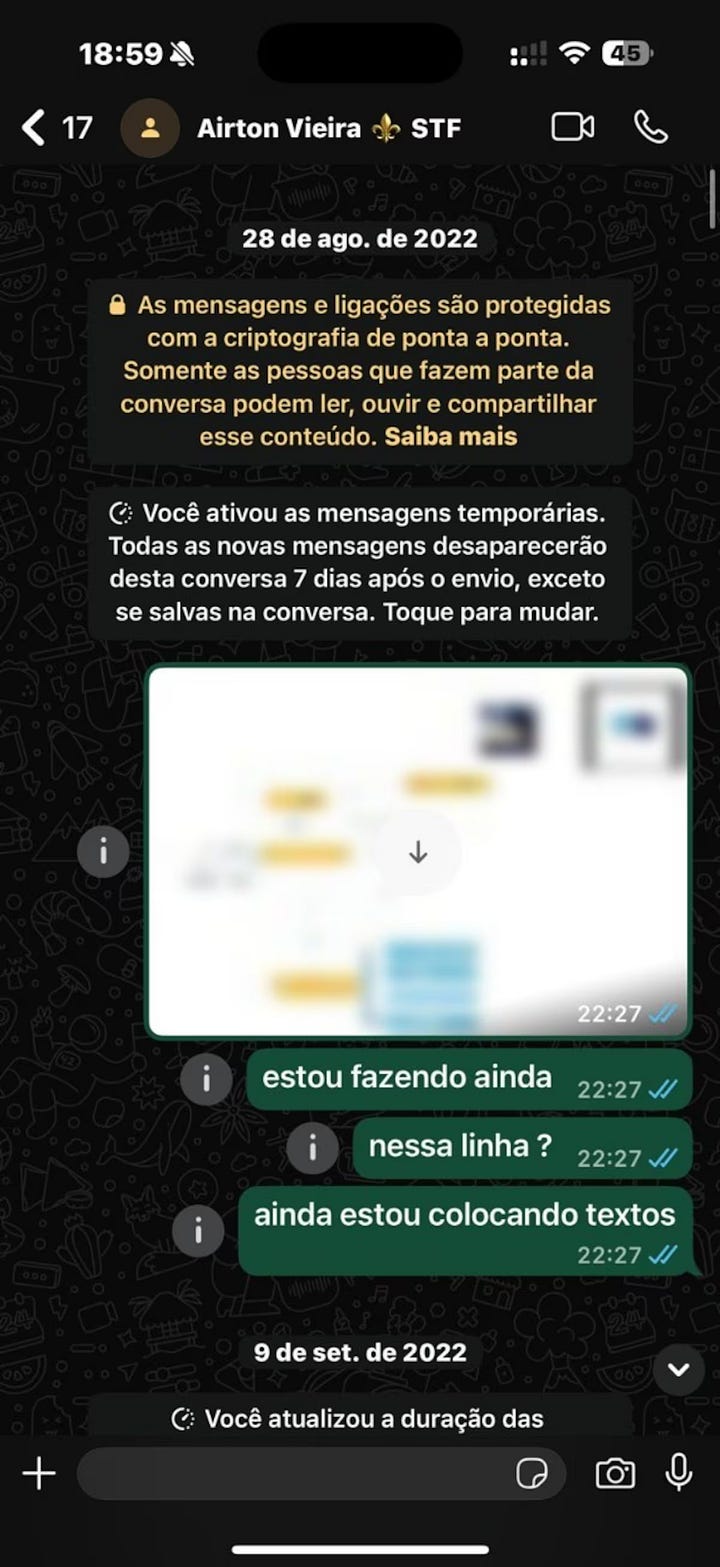

Even before realizing he had already received the file, Tagliaferro forwarded a message, apparently from someone close to Moraes, with further instructions. Previous Vaza Toga leaks showed he took guidance from two judges: Marco Antônio Vargas, an auxiliary judge at the TSE who once texted that he wanted to “send thugs” to capture journalist Allan dos Santos (then in the U.S. after being added to the fake news inquiry); and Airton Vieira, Moraes’s senior aide at the Supreme Court and his right-hand man. In Senate testimony, Tagliaferro pointed to Vieira as the one who ordered him to falsify reports to give the operation a veneer of legality.

According to Tagliaferro, Moraes himself was unaware that Vieira had delegated the task to him. He added that Vieira instructed him not to mention it. One such message read: “If he at least gets the group screenshots, we could cross-check with our inquiries to see if we can rope in more people to strengthen the case. Yes. Talk to Eduardo. Then we’ll decide if it’s worth waiting.”

This exchange is telling. It shows that even after the raids had already been executed, Moraes’s office was still scrambling to find retroactive material to bolster the accusations. In other words, the WhatsApp screenshots were not just supporting evidence — they were the raw material used to backfill a narrative and justify the August 23 operation.

Possible Illegalities

Attorney Richard Campanari, a specialist in electoral and civil law and a member of Abradep (Brazilian Academy of Electoral and Political Law), argues that the case reveals a serious breach: the rupture of the chain of custody of evidence, as established in Articles 158-A to 158-F of Brazil’s Code of Criminal Procedure. This mechanism, he explains, was designed precisely to ensure that any trace of evidence — documents, objects, or digital media — is collected, preserved, and tracked until its presentation in court, preventing tampering.

“What we see here is the exact opposite: WhatsApp screenshots would have been handed over informally to a minister’s office, without a formal seizure record (in violation of Article 158-B), without an official forensic examination, without an integrity hash, and without any formal protocol. In other words, there is no way to guarantee that what was presented as ‘evidence’ was authentic and not altered,” he says.

According to Campanari, when such material is used to justify restrictive judicial measures — such as freezing social media accounts, search and seizure operations, or financial constraints — it violates constitutional guarantees: the duty of judicial reasoning (Art. 93, IX of the Constitution), due process of law, the right to defense, and the adversarial principle (Art. 5, LIV and LV). In practice, these elements are null and void (Art. 157 of the Code of Criminal Procedure) and taint everything derived from them, under the so-called “fruit of the poisonous tree” doctrine.

The lawyer stresses that the allegation of retroactively fabricated reports makes the situation even worse. Creating documents after the fact and backdating them violates the principle of legality (Art. 5, II of the Constitution) and procedural good faith (Art. 5 of the Civil Procedure Code, applied by analogy in criminal proceedings). If proven, such conduct may amount to ideological falsification (Art. 299 of the Penal Code) and abuse of authority (Law 13.869/2019), since judicial decisions would have been based on artificial records.

“In short, this is not merely a procedural formality. When the judiciary relies on evidence without proper custody and on reports produced after the events, it not only compromises specific investigations but undermines the backbone of the rule of law. After all, without legitimate evidence, the judicial process ceases to be an instrument of justice and becomes a tool of arbitrariness,” he says.

Finally, Campanari notes that if it is proven that the minister knew of the illegality and still used such evidence, the consequences could range from the nullification of cases to criminal liability — and even a potential impeachment for crimes of responsibility. “This is more than an irregularity; it is a grave violation that strikes at the legitimacy of the judiciary itself,” he concludes.

What the Parties Say

At the time of publication, we had not received responses from Letícia Sallorenzo, Lucas Mesquita, or the press offices of the Supreme Court (STF) and the Superior Electoral Court (TSE). However, we include here a generic statement issued by Moraes’s office in response to Tagliaferro’s testimony before the Senate:

*“The office of Minister Alexandre de Moraes clarifies that, in the course of investigations under Inquiry 4781 (Fake News) and Inquiry 4878 (Digital Militias), in accordance with court regulations, various orders and requests were made to numerous bodies, including the Superior Electoral Court, which, in exercising its police powers, has authority to prepare reports on illicit activities such as disinformation, electoral hate speech, attempted coup d’état, and attacks on democracy and institutions.

The reports merely described unlawful posts published on social media, objectively, given their direct link to the digital militias investigations.

Several of these reports were filed in these and related investigations and forwarded to the Federal Police for further action, always with the knowledge of the Office of the Prosecutor General. All procedures were official, lawful, and are fully documented in the ongoing Supreme Court inquiries, with full participation of the Prosecutor General’s Office.”*

This article is protected under Article 220 of Brazil’s Federal Constitution, whose fundamental precepts were recognized by the Supreme Court in rulings ADPF 130 and ADPF 601, as well as Articles 13 and 14 of the American Convention on Human Rights (San José Pact). A Investigação upholds the right of reply as established by Law 13.188/2015, subject to legal review.